Writings

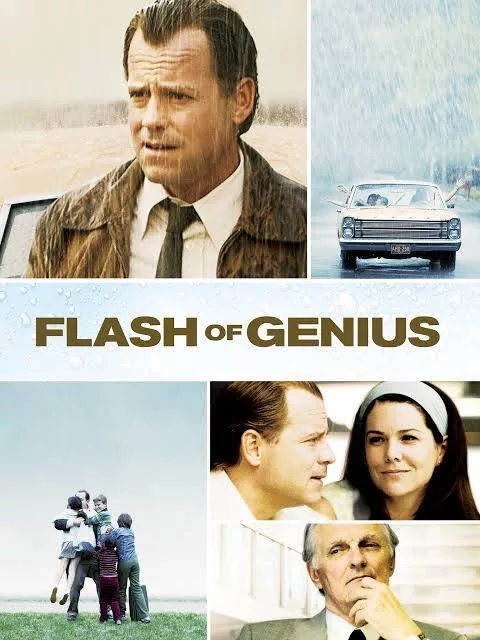

A cursory glance at the topics below doesn’t suggest an obvious journalistic beat. But a closer inspection of these pieces reveals a common theme. They are full of engineers. From the mechanical and structural engineers in “Flash of Genius,’ “The Tower Builder,” and “Fragmentary Knowledge” to the software engineers in “Email from Bill” and “My First Flame,” to the pop star engineers in “The Song Machine” and “Factory Girls,” to the machine learning engineers in “Ancient Library” and “The Next Word,” I keep returning to brilliant, ambitious, and entrepreneurially inclined engineers in my work. “The Spinach King” not only continues this theme, it explains its origins – the men in my family.